Fibrillation is defined as “the rapid, irregular, and unsynchronized contraction of the muscle fibers of the heart.” I’m talking about that type of fibrillation in this post, but many a screenprinter has felt like they are going to have a heart attack over the type of fibrillation that happens to t-shirts.

Fibrillation in screenprinting is when the fibers of a shirt stick through the ink giving a shirt after washing a faded or even hairy look. Yesterday’s nice brightly printed shirt looks faded in tomorrow’s wash and most days that is not a good thing.

My pal Mike Beckman once said to me, “what is so difficult is that unfortunately usually the better the shirt quality the more it fibrillates!” Here is the dilemma: everybody wants softer and softer shirts and thinner and thinner ink deposits and softer shirts tend to fibrillate more and thinner ink deposits tend to let the fibers come through. This all leads to screenprinter distress

Can you just buy better shirts? No, not usually. You can try to buy shirts that fibrillate less. I am not a garment construction expert, but I can tell you that some of the nicest shirts that are soft seem to fibrillate the most. This is in either of the ways I hear people talking about soft – A: In the plush sense of being thick fabric and maybe ring spun or carded cotton, or B: Soft in the thin tight yarn silky smooth sense of soft. Lots of cotton fiber or lots of cotton yarn and either way you are talking about lots of cotton fibers that are just waiting to break through the ink deposit and make the print look hairy and faded. Almost everyone wants soft shirts so this idea is highly impractical

Can you predict fibrillation? Besides the good guess that the nicer the shirt the more it is possible, you probably should find out before your customer returns 1000 shirts on Wednesday that he test washed and wants you to make sure the 999 will be ok for his event on Saturday. Once you didn’t deal with it during the printing you are pretty much up the creek without a paddle. You need a fancy testing device we call a washer and a dryer.

Hey, make your employees happy and let them do some laundry and throw in a test shirt every once in awhile and particularly when dealing with a brand of shirt with which you are unfamiliar. IMHO there is no substitute for doing what your customer is going to do, which is wash and dry the shirt. If possible wash it a couple times because cotton fibers can continue to break lose with repeated washings. Note: Don’t confuse fibrillation with the ink not being cured. Fibrillation will look faded across the whole shirt and under close (or even not so close) examination look like fuzz all over the surface of the print, whereas uncured ink will have come off in a “splotchy” uneven way.

This is where I could insert a long discussion of whether increased fibrillation problems are caused by the ink or the shirt. Position one (as maintained by ink companies) is that it is the fault of shirt manufacturers now making shirts with yarn that untwists and in other ways comes undone in the wash. Position two (as maintained by shirt manufacturers) is that inks have too much filler, not enough of the right quality pigment, and are not elastic enough and therefore don’t adequately keep the fibers done. This argument chases its tail and reminds me of PC vs. Mac arguments that never get settled (even though Mac’s are better.) At the end of the day as printers we have to give our customers shirts that are not fibrillated, not give our customers excuses for why they are fibrillated. By the way, this argument played out in a way where just about everyone believes it is the fault of the shirts, but I actually believe the fault is mostly with the ink. An elastic film of ink that covers the fibers should hold them down after washing.

So you know that fibrillation is going to happen with certain shirts, now what? If you are printing pastel colors on white shirts, honestly the fibrillation will be present if you look at the shirt with a magnifying lens (loupe) but won’t be noticeable to the naked eye. If you can’t see it, don’t worry about it unless you are dealing with some jackass retailer with some bible of standards. For regular customers don’t worry unless you can really see it. The most noticeable fibrillation will be with large areas of dark ink on the lightest colors of shirts (particularly white) and that is where your effort to reduce fibrillation is going to have to be directed.

One solution is to just print more ink down, to lay such a thick coating down that the fibers are kept under a continuous film of ink. It is possible in many cases to just use a good ink company’s good ink and lay down enough of an ink deposit to keep the fibers down. As in so many things in life, you are shooting for moderation. Too little ink and the fibers poke their nasty selves through the ink, and too much ink and you will have a harsh “plastic” feeling print with what is known as a bad “hand.” This course of printing an even moderate coat of ink is of course always aided by having a well-maintained press with level platens, and level well-tensioned screens. What you are looking for in a “good” ink is creaminess, long body (it will stretch without breaking), good crock resistance (when you rub a blank shirt on the cured surface it doesn’t come off,) it doesn’t build up on the back of the screens, and it lays consistently flat when you print it. We use Rutland inks in my shop because they most closely approximate the perfect ink.

How much ink is just right? Ok, get out your micrometers….yeah I thought so, you forgot your micrometers at home. Print shirts consistently and make notes about your consistent methods and on what shirts and then use your advanced testing apparatus (take a look again at that washer and dryer.) You will get to know that if you use the same squeegee, angle, off contact, mesh, coating technique, ink, flood stroke…then you don’t get fibrillation.

Ok, no matter what you do you are getting fibrillation, now what? Or you aren’t getting fibrillation but your print has to be nearly bulletproof in order to keep the fibers down. I spoke with two of the best printers I know about this. Mike Beckman (inventor of high density ink) and Brian Lessard (winner of many industry awards for prints when he worked at Mirror Image) who both acknowledged that some shirts just present a tough problem.

Both acknowledged that one possibility is always to print multiple thin layers of ink, ideally three. If you have room on your press you print flash print flash print and do a layer that penetrates the shirt, one that locks down the fibers at the surface, and a final layer that covers it all. This photos shows a print that has a relatively soft hand (you will have to take my word for that) but held down the fibers well compared to prints we had tried with just two layers.

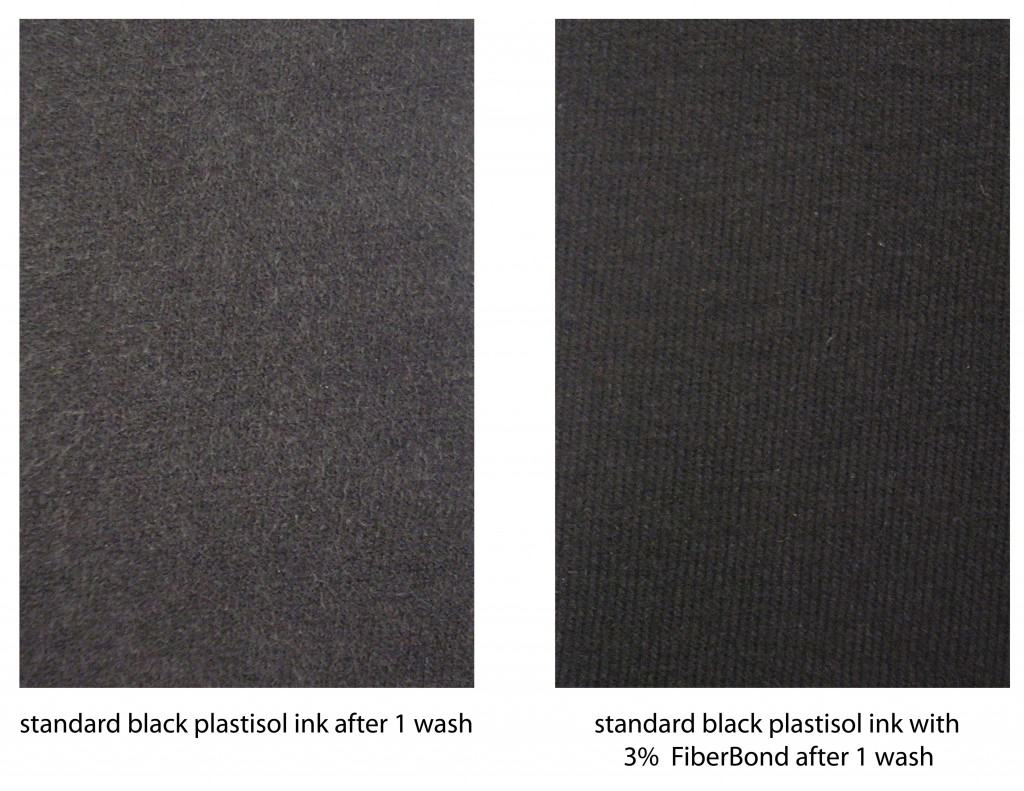

Brian works for the ink company Rutland and ran some tests on an ink additive they call fiberbond that basically glues the fibers down. It is added to your plastisol inks and basically glues the fibers down. Here are photos of before and after washing and the effectiveness of such an approach.

The downside to fiberbond or equivalent products from other companies is it lessens the pot life of the ink and you cannot re-use the ink the way you would with a normal plastisol.

Another possibility is to put down a curable clear ink such as primer clear which also can keep fibers down before the print even goes on. This approach can particularly work when for some reason in your print order the black ink cannot go last and might pick up on the backs of other screens causing even more fibrillation than normal.

Another approach is to print a clear over the whole design at the end of the print order. The downside is that it can leave more of a gloss finish but the upside is that you get bright colors to stay bright after repeated washing and you stop all fibrillation. You create a screen that covers all the other screens and then after all colors are printed you flash and then print a clear curable base ink and then put the shirt in the dryer. I recently saw a shirt that we printed (it was a process print on white and process prints particularly tend to fibrillate) at Mirror Image over ten years ago. It was on the back of a construction worker and the Sam Adam bottle print still looked good despite the shirt looking visibly beat up and even at a distance sort of fuzzy and well… fibrillated. Ink manufacturers seem to recommend printing such a final clear through a 230 mesh. On a good press with good technique in our shop we sometimes use up to a 305 mesh and get less gloss to the final clear but just enough clear ink down to keep the fibers in place.

Yet another approach to beating fibers down is to use a penetrating water-based ink. This can work well with white shirts, which are the shirts that show fibrillation the most. Water–based ink can penetrate and color the fibers of the shirt so even if they pop up they are mostly already the proper color. Water-based inks despite new improvements of course have the usual problems of drying in the screen, not being re-useable, and difficulties with coverage on dark or even medium shades. On light colors you would have good luck with water-based inks beating fibrillation. A trade off is that you will probably have difficulties with ink color matching since the color of the fibers is not entirely covered by the ink color.

A friend says at his shop they often have fibrillation to deal with because of the fine cotton shirts they print. They also often have customers with very demanding testing for fibrillation that can include having to stand up to 15 washings. To pass these tests and to combat fibrillation they generally do a first down clear and use a longer bodied (roughly translated thicker, more elastic) clear base. He finds that even the best printer with the best efforts can’t keep fibers down and has to resort to using a first down clear with what he acknowledges are his favorite shirts, the plush ring spun cotton nice soft shirts. “They are the best to wear, but sometimes the most difficult to print.”

There is a delicate balance that is sought (Zen and the art of screenprinting anyone?) to get just enough ink down to have the print keep the fibers down but at the same time not have a print have a harsh hand. I think it is clear (pun intended) that armed with clear inks the printer whether going over or under the print can strike a balance and keep the fibers in check better than just printing thicker coats of pigmented inks.

Have you ever used an “Action Roller Squeegee” to reduce fibrillation? Here’s a link to a video demonstration:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cH0W7XMBXtQ

It looks like a good solution.

Action roller squeegees, blank screens in the print order and a hard squeegee, etc all serve to push the fibers down and push the ink into the fibers, but the ink still has to keep the fibers down or you will get fibrillation after the shirt is washed.

What is a good clear base?

🔍

Rutland Primer Clear can be used under or over. Besides keeping fibers down for washability, it also can catch a lot of lint and prevent lint spots.

Do you have a recommendation for a low cure first down clear? Around a 270F cure?

It really depends on the ink brand and the thickness of the print. Talk to the ink manufacturer. 270 sounds low, I think you have to get it to 320 in most cases.